Long-term care workers have, in many countries, become the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Asian region is no different. As the region grapples with an increasingly aging population, the pandemic has prompted new policies that aim to support long-term care workers, particularly migrants, in supporting older people.

These interconnecting dynamics—between long-term care, migration, and COVID-19—are the subject of a new paper, published today, by the Center for Global Development (CGD) in partnership with GaneshAid.

Increasing demand for long-term care

Asia is home to some of the world’s most rapidly aging populations. Over the past seven decades, total fertility rates (TFR) have fallen steeply and life expectancy has jumped dramatically. Thanks to better healthcare and basic standards of living and sanitation, both men and women in these countries can now expect to live well into their 80s, if not 90s.

These trends have led to a higher old-age dependency ratio (Figure 1), which puts more pressure on younger people to care and provide for older people. Yet younger people are also eschewing these traditional roles at an increasing rate, seeking to move to cities and participate in the labor market (especially true for women).

Figure 1. Old-age dependency ratio growth, 1950-2050

Source: Own graph using data from United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) 2019. “World Population Prospects 2019

This is leading to a large unmet need for long-term care throughout Asia; one survey found 50 percent of older people in the region weren’t getting the care they need. This gap is more acute for those living in rural areas (especially in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam); women (especially in Singapore, Japan, and South Korea); and those living in poverty (especially in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam).

As a result, Asia is in need of millions more care workers. Ideally, there should be 4.2 formal long-term care workers per 100 individuals aged 65 or over (based on this recommendation, Asia and the Pacific as a region is lacking 8.2 million care workers). Japan has just four care workers per 100 older people, South Korea has fewer than two, and China has only just over one. As a result, much of the long-term care in these countries is unpaid and provided by family members, meaning people are less likely to be able to work, and reducing the overall labor force participation.

Meeting this demand through migration

Whether it’s due to the wages and working conditions offered, perception of the care profession, or absolute labor scarcity, the demand for long-term care in Asia is not currently being met through local recruitment. As a result, many countries have turned to migrant workers to fill the gap.

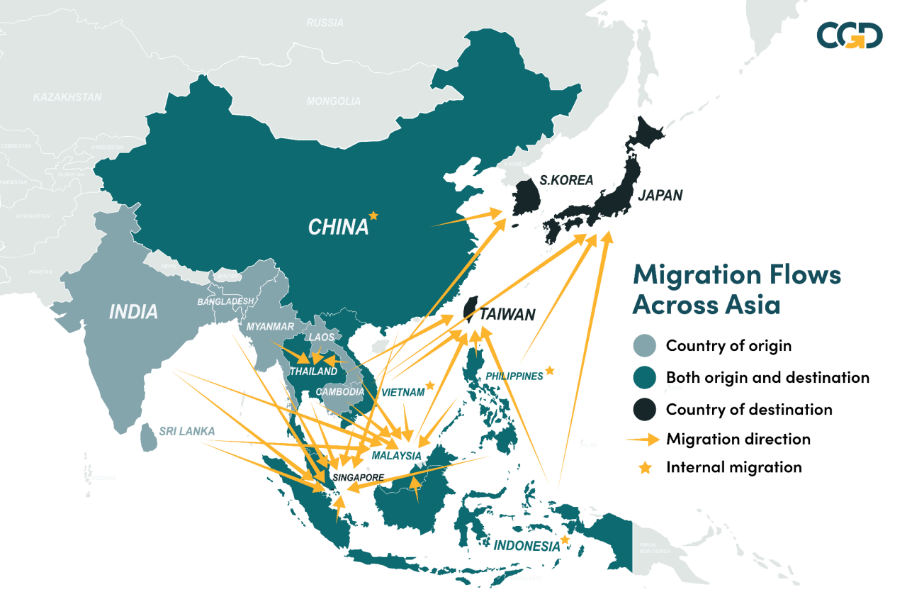

Most migration for long-term care occurs from poorer Southeast Asian countries (such as the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam) to richer East Asian ones (such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Long, and Singapore) (Figure 2). The Asian region is unique in housing some of the only countries to proactively create immigration pathways for long-term care.

Figure 2. Patterns of migration for long-term care

For example, Japan created a new ‘Care Work Visa’ (kaigoryugaki) in 2017 to provide access to migrants who had secured employment in the care sector in Japan; Singapore brings in migrant long-term care workers through their ‘Foreign Maid Scheme’ and ‘S-Pass’; and Taiwan introduced their ‘Foreign Live-in Caregiver Program’ in 1992. The increasing prevalence of such pathways, and the general shortage of health workers globally, has led many in the international community to explore how such migration could be regulated and improved. Such discussions started at the same time as COVID-19 rocked the region.

Lockdowns prevented many migrant long-term care workers from physically sending money home, despite money transfer organizations being designated as essential services. Despite this, remittances throughout the region largely remained strong. Many countries curtailed freedom of movement, forcing long-term care workers to work on their rest day, lest they bring COVID-19 into the house.

Migrant long-term care workers were frequently worried about accessing health care in their country of destination, or were even barred from doing so. Especially in the early days of COVID-19, access to information, testing, and treatment was impeded for migrants.

During the pandemic, many migrants abroad sought to return to their countries of origin due to a fear of COVID-19, job losses or expected job losses, and the expiration of work permits. While some countries—such as the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia—supported their overseas workers with repatriation flights and other forms of assistance, others did not.

On a more positive note, several countries, wary of the impact of border restrictions and changing employer demand on the rights of their migrant workers, made steps to shift their employment conditions. South Korea granted three-month extensions to those with expiring visas; Singapore extended expired work visas for two months; and Taiwan barred entry to new migrant care workers but implemented successive six-month extensions for existing workers.

Others focused on the rights of migrant workers, especially migrant domestic workers, to change employers. Some countries explored the opposite, enacting regularization, and legalization campaigns, recognizing the impact that undocumented workers could have on labor shortages during the pandemic.

What’s next?

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of migrant workers to long-term care systems throughout Asia. If countries in the region, particularly countries of destination, are to reduce their unmet need for care, expanding immigration for long-term care in an ethical, sustainable, and rights-respecting way will be required.

These efforts should be undertaken alongside reforms to the long-term care system itself, focusing on how the system is financed, structured, and resourced. Finally, the pandemic has shown us how migrant care workers should be supported, both during and beyond crises, lessons that must be kept in mind throughout any reform efforts.